As Wes Craven’s most recent biographer, I was taken not only by his creative skill in coming up with new ways to scare us, but also by the spiritual qualities and conflicts that were often in play during many of his films. With all of that in mind, here’s something I wrote for the Tulsa World’s Jimmie Tramel when he asked me for comments following Craven’s passing:

It seems to me that the genius of Wes Craven lay in his ability to bring the terror closer to a viewer than ever before, using an innovative technique that’s often been referred to as “rubber reality.” Basically, this means that when you’re watching the action on the screen, you’re never sure if what you’re seeing is supposed to be taking place in the real world or the dream world. This intentional confusion of dreams and reality keeps you off-balance and skittish, pulling you into a weirdly intimate place where anything can happen — just as a dream does. I mean, what’s more intimate than a dream?

I remember the first time I became aware of what he was doing, and it chilled me to the marrow. It’s kind of a throwaway scene in 1984’s Nightmare on Elm Street, his breakthrough picture, in which the camera pans down a high school hallway, with kids going back and forth to classes — and there’s a goat, standing by a locker, with no one paying any attention. It was exactly the kind of thing you’d see in a dream, and I suddenly knew we were dealing with something new here, and that the ante had been upped for horror-film audiences.

To my mind, this approach was perfected in Wes Craven’s New Nightmare(1994), which I think is his best picture. In it, reality warps back and forth and back again, as he and his two Elm Street stars, Robert Englund and Heather Langenkamp, play themselves, haunted by manifestations of the roles they’ve played. It sounds confusing, but it’s freaking brilliant.

I should also say here that a tip of Freddy Krueger’s fedora needs to go not only to actor Englund, who helped make the Krueger character such a fright-film icon, but to Tulsa’s own Heather Langenkamp, who brought an immeasurable amount of charisma and likability to her roles in Craven’s two greatest films. (And yes, the Scream pictures were pretty terrific too, with Craven leaving behind the idea of rubber reality to explore the potential of self-reference, in which the characters in a horror film refer to characters in horror films. It was very clever, but I just didn’t think it was as effective as the approach he took in Elm Street and New Nightmare.)

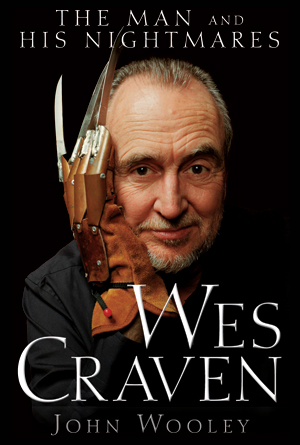

I was delighted to be able to really dive into this stuff in my Craven biography, Wes Craven: The Man and His Nightmares. I would’ve been even more delighted if an event trumpeted by a Hollywood Reporter story back in the mid-‘80s had come to pass. It said that Craven’s next picture would be Old Fears, based on a novel he had just optioned. Old Fears was written by my friend Ron Wolfe and me, and while Craven kept it under option for a year or so and we cashed a couple of nice checks as a result, the film version never happened.

About 10 years after Craven took out the option, when Scream was getting ready to hit the nation’s theaters, I did an phone interview with him in my capacity as an entertainment writer for the Tulsa World. He was congenial and articulate, as he always seemed whenever I talked to him, and when I reminded him I was the co-author of Old Fears, he said, “Oh, sure. Did that picture ever get made?”

I wish it had. And I sure wish he’d made it.